In the last post, I summarised what we know about the origins of the French family, and reported what I’ve managed to find out about my 3rd great grandfather Frederick French (1810 – 1887), a Dorset-born Stepney shoemaker, and his wife Sarah Elizabeth Bull (1813 – 1857). I noted that Frederick and Sarah had eight children, and in this and forthcoming posts I want to explore what became of them.

I trace my descent from Frederick and Sarah’s sixth child, also named Frederick, who was born in 1847 in Limehouse, in the East End of London. At the time of the 1851 census, when he was four years old, Frederick French junior was living with his parents and siblings at 5 Wilson’s Place, off Salmon Lane. By 1861, the family had moved to Grenada Terrace, on or just off Rhodeswell Road. Now aged 14, young Frederick was already working alongside his father as a (presumably apprentice) shoemaker.

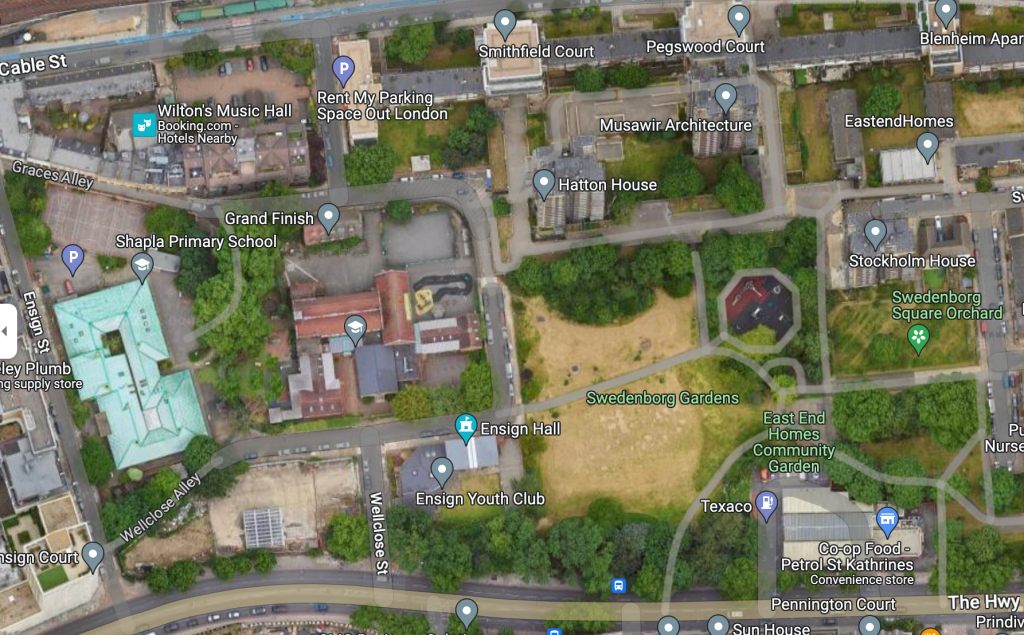

Part of Edward Weller’s 1868 Map of London (via https://london1868.com), showing Canal Road and Burdett Road

On Christmas Day, 1867, 20-year-old cordwainer Frederick French married Emily Hindley at All Saints church, Poplar. Both parties gave their address as Canal Road, which ran alongside the Regents Canal, to the south of Mile End Road. Born, like Frederick, in Limehouse in 1847, Emily was the fifth of the seven children of ship chandler William Hindley and his wife Mary Affleck. There are records of the Hindley family in both the 1851 and 1861 census records, though I’ve yet to find a matching record for 1841.

The Hindleys

In 1851, we find 30-year-old labourer and ship chandler William Hindley and his 30-year-old wife Mary, at 3 Kirk’s Row, Limehouse, with their children William, 11, John Charles, 8, Mary Esther, 6, Emily, 4, Jessie, 2 and a 5-month-old son who is ‘not yet named’. By 1861, the family is living at 2 Rhodeswell Terrace, and William senior is working as a sailmaker and warehouseman. Other members of the family are similarly employed: son William, 21, is also a sailmaker, while wife Mary and daughter Mary are described as flagmakers. Emily, 14, and Jessie, 12, are said to be ‘scholars at home’. The child who was 5 months old in 1851 seems not to have survived, but there are two new children: Ellen A, 8, and Sydney, 1.

Sailmakers

The Hindley family was probably the original source for the name Jessie that would be passed down through my father’s family. Frederick and Emily French would name one of their daughters Jessie, and another of their daughters, my great grandmother Mary Webb née French, in turn gave a daughter the same name (she also gave my grandmother the middle name Emily, after her own mother). My father’s sister – my late Auntie Kit – was christened Katherine Jessie May Robb (another sister, my late Auntie Grace was Grace Mary Emily).

William Hindley and Mary Affleck were married on 5th November 1837 at All Saints, Poplar. Mary Affleck’s father was said to be engineer Samuel Affleck and one of the witnesses to the marriage was her mother Esther (or Hester) Affleck: both are Christian names that the Hindleys would give to their children. Mary Affleck was born on 14th June 1816 and christened at St. Dunstan’s, Stepney. Going back still further, we find that Samuel Affleck married Hester Gunter on 16th January 1814 at St. Mary’s church, Lewisham. Although both were resident in the parish, Samuel is said to have been born in ‘Galloway, N. Britain’ and Hester in Coaley, Gloucestershire. At Scotland’s People I came across a baptismal record from 1794 for Samuel Affleck, son of mason Robert Affleck, in Dumfries, Galloway.

In 1871, four years after Emily Hindley married Frederick French, her parents William and Mary were living in Cowley Road, Wanstead. William was now a retired warehouseman and living with them were William junior, Helen and Sidney. By 1881 Mary had died and widower William, now a clerk in a coal office, was still living at Cowley Road with Helen and Sidney. At the same date William junior, a sail maker, was living with his wife Sarah and children Alice and Charles at 4 Alfred Terrace, Limehouse. I haven’t found a record for them in the 1891 census, but they were still in Limehouse in 1901.

The children of Frederick and Emily French

Frederick and Emily French’s eldest daughter, Emily Mary, was born on 25th November 1868. Their eldest son, Frederick William, was born two years later, in 1870. At the time of the 1871 census, the young family was living at 13 Rhodeswell Road, in the same house as Frederick’s brother William and his wife and young family. As I noted in the previous post, the two French brothers appear to have gone into business together as shoemakers.

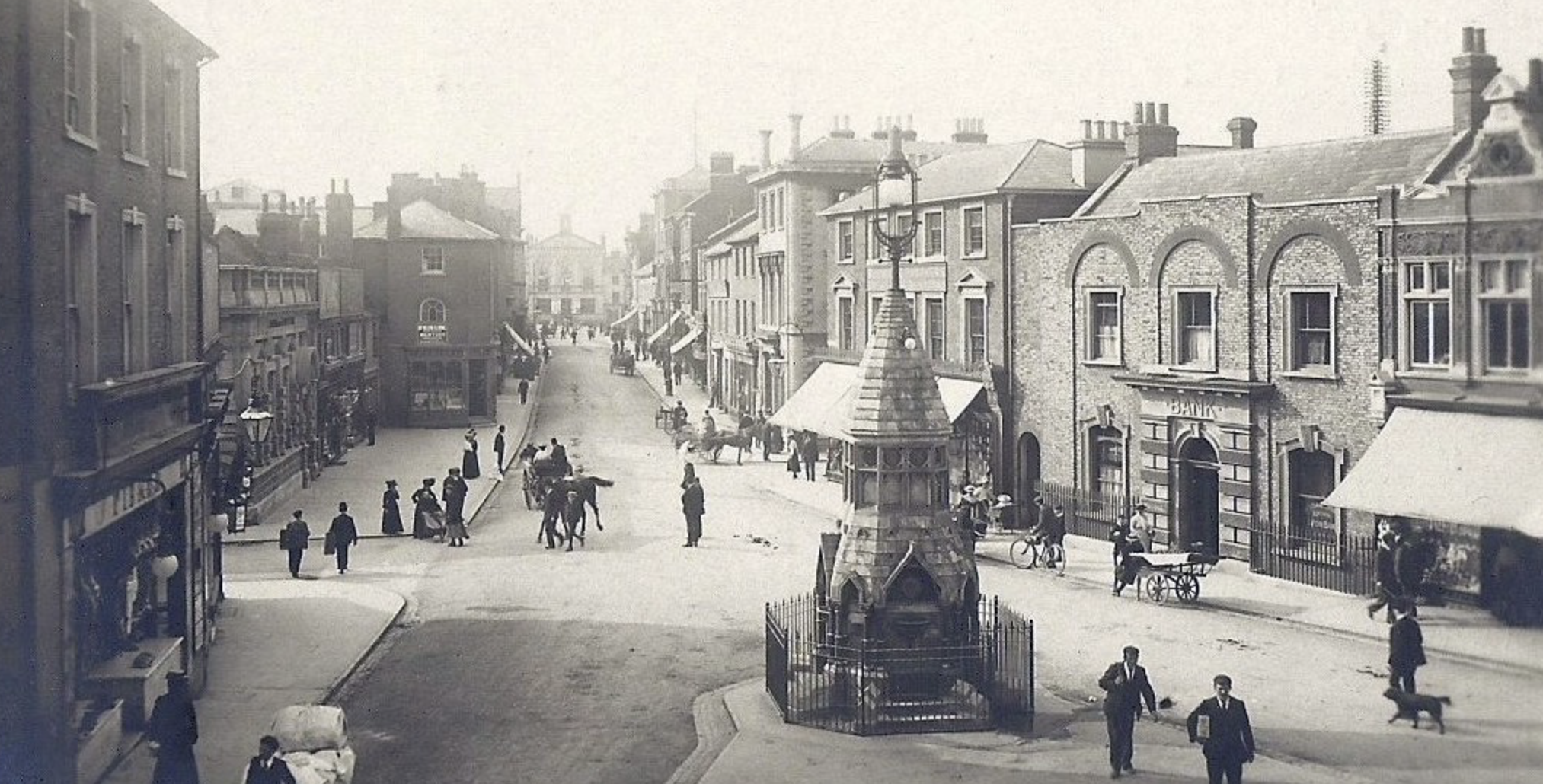

Shoemaker’s shop

The next decade saw the births of four more children. A second son, Seth, was born on 19th January 1872 but not christened until 18th April 1886, when he would have been fourteen, at St Luke’s, Limehouse. He was obviously named after Frederick’s brother, who had died in 1856 at the age of 22; while he in turn must have been named after his mother’s brother, Seth Bull, who also died young. On 11th July 1873, Frederick and Emily’s daughter Mary was born: she was my great grandmother. Three more daughters followed: Jessie, born on 23rd January 1876, Caroline in 1879, and Katherine in 1881.

The 1881 census finds Frederick and Emily French, now aged 34, with their seven children, still living at 13 Rhodeswell Road, together with Frederick’s brother William and his family. Three more children would be born before the next census: Grace in 1883, William Hindley in 1884, and Francis in 1887.

By the time of the 1891 census, Frederick and Emily had moved to 92 Burdett Road, a little to the north of Rhodeswell Road, where Frederick’s brother William and his wife Katharine were still living. Frederick is now described as a boot and shoe manufacturer, and he and Emily still have all ten of their children living with them, a number of whom are working for the family business. Emily, 22, is described as a tailoress, as is Mary, 17, while Frederick, 21, and Seth, 19, are both working as boot riveters. Also living at home are Jessie, 15, Caroline, 12, Katherine, 10, Grace, 8, William, 6, and Francis, 4.

The French family in the 1891 census, at 92 Burdett Road, Mile End Old Town (via ancestry.co.uk)

On 6th August 1893 Seth French married Edith Alice Buckle, daughter of William Buckle, a police constable, at the parish church of St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney. Curiously, Seth gave his address as 13 Rhodeswell Road.

In 1894 Frederick and Emily French’s eldest daughter, Emily Mary, married Irish-born police constable Richard Donovan, who I believe was a widower.

On 8th August 1897 Mary French married decorator George Webb, son of another decorator of the same name, at the church of St Paul, Bow Common. Bride and groom both gave their address as 92 Burdett Road. George and Mary Webb were my great grandparents.

In 1901, the Frenches were still at 92 Burdett Road, which the census record describes as a bootmaker’s shop: it was sandwiched between a lead merchant and a corn chandler, and other premises in the street included a wardrobe dealer, a tobacconist and a builders’ materials shop. 54-year-old Frederick is described as a bootmaker and an employer. Sons Frederick, 30, William, 16, and Francis, 14, are also described as bootmakers, while daughters Jessie, 25, Caroline, 22, Katherine, 20, and Grace, 18, are working as tailoresses. All are said to be working at home.

At the same date, Seth French, his wife Edith and their 5-year-old daughter, also named Edith, were living at 67 Southwell Road in Leytonstone. Seth was working as a boot and shoe maker, Edith as a waistcoat maker, and they had a lodger, Frank Stevens, who was working as a boot finisher. My great grandparents George and Mary Webb had set up home at 32 Coutts Road, an address they shared with at least one other family. George was now employed as a labourer at a gas works, and the couple had two children, Mary Emily Elizabeth, aged 3 (my grandmother) and Jessie Caroline, 10 months. Emily Mary and her husband Richard Donovan were living in Quickett Street, Poplar, with their children, a number of whom must have been from Richard’s first marriage, including Margaret Mary, 19, Helen Josephine, 17, and Richard Michael, 5. There were also three younger children, presumably the product of Richard’s marriage to Emily: Emily Mary Margaret, 4, Fred Charles, 2, and Theresa Jessie, 1.

On Boxing Day 1901, Frederick and Emily French’s daughter Jessie, 25, married Frank Robert Clifford, a Kent-born gardener, and the son of Edward Clifford, also a gardener, at Holy Trinity church in Stepney. By the time of the 1911 census, they were living in Melford Road, Leytonstone, with their five children: Frank, 8, Jessie, 7, Seth, 5, Ella, 2, and Robert, who was just a few weeks old.

I’m not sure what became of Jessie’s sister Caroline. She may be the Caroline French who married a William Fisher in 1904 or 1905, and by whom she had two children, Edward and Philys, before his early death. This Caroline Fisher, a widow of 34, and her children could be found living at 39 Burdett Road in 1911. Similarly, I’m unsure of what became of another sister, Katharine, also known as Kitty, except that (according to information from a family member) she went to live in Ireland, probably remained single, and may be the person of that name who died in Barnet in 1965.

I’m still trying to discover what became of Frederick and Emily’s son Frederick William. He must have got married some time after 1901, but to date the only definite record I’ve found for him is from the 1939 England and Wales Register, which finds Frederick William French, a 69-year-old boot repairer, and Mary D. French, of the same age and presumably his wife, living in Whitstable, Kent. According to information shared by a family member, he and Mary had two daughters, one of whom was named Stella.

On 25th July 1904 William Hindley French married Alice Maud Beecham, son of crane driver John Beecham, at the parish church in Bromley St Leonard. They seem to have had one son, Henry, before Alice’s untimely death in January 1911. The census of that year finds William, a widower at just 26, living alone in Odessa Road, Forest Gate.

In about 1910, Francis – also known as Frank – French married a Devon-born woman with the Christian names Lily Rose (I’ve yet to find a record of their marriage). In 1911 they were living in Brunswick Road, Leyton, with their 2-month-old baby, Lily Emily. Frank was working as a bootmaker.

Frederick, Emily and Grace French in the 1911 census record (via ancestry.co.uk)

By 1911 Jessie’s parents Frederick and Emily French, now aged 64, had moved to Crownfield Road in Stratford, where they were both still working as boot repairers. 28-year-old Grace is now the only one of their children still living at home. Emily Mary and her husband Richard Donovan, now working as a night watchman, were still living in Quickett Street, where their family now included a 6-month-old baby, Robert Jeremiah. Seth French and his wife Edith Alice, both now 39, are still at the same address in Leytonstone, with their two children Edith Ethel Grace, 15, and Minnie Dorothy, 7. Boarder and boot finisher Frank Stevens is still living with them. Mary and her husband George Webb, now working as a machinery oiler at a brewery, and both aged 37, have moved to 39 Perth Road in Barking, where they are living with their five children: Mary Emily Elizabeth, 12, Jessie Caroline, 10, George Frederick, 8, Charles Joseph, 6, and Alfred Arthur, 4.

According to some records, Frederick French died in 1917 at the age of 70, and Emily French née Hindley in 1918 at the age of 71.